Corporate picture, 1960’s

I had a fractured relationship with my father, Wayne Franklin Fry, and I’ve come to realize that a large part of that was due to the toxic atmosphere (literally) of my father’s job in the machine felt industry. He rose through the business to eventually become plant manager of Albany Felt Company at its South Carolina facility. They manufactured the large felt “belt” that ran underneath the wet wood pulp slurry as it became paper, removing the moisture along the way. But, in the 50’s and 60’s, I’m sure the chemicals used to take the raw wool and press it into this felt were highly toxic, and there were few environmental standards back then. I remember the stench of the plant in Albany.

My father started suffering blackouts, starting with an unexplained car accident driving home from work one night. As our family started to notice these episodes, my dad would maintain consciousness but not know who he was, who we were and ask, “What do I do now?” It became common when my father would get upset with some emotional situation. We became fearful of getting him mad and we avoided confrontation at all costs. One evening at dinner, he blacked out while eating some food and I had to lift him upside down to dislodge the meat from his throat (pre-Heimlich). I’m also sure that part of his problem was his own avoidance of emotions growing up, in a mother-less household with only his father and Uncle Harry during the 20’s and 30’s.

Wayne and Doris wedding, June 30th, 1944

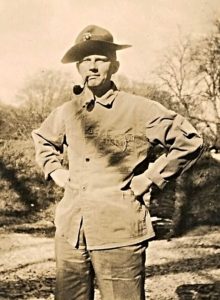

Camp Lejeune, lieutenant in Marine Corps.

My dad joined the Marines at the beginning of WW II, served in Ireland and as a drill master at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. He returned to his home town in Bristol, married my mom Doris Rachel Hendricks in ’44 and moved to the Albany area to start at Albany Felt Co. and began a family with my older sister Christine (’47) , me (’50) and my younger sister, Janet (’54).

My dad in his later years, in the ’90s.

I remember my father enjoying our young family and a circle of bright, witty friends, singing with a men’s chorus The Mendelssohn Club and acting with the local theater troupe The Willett Street Players at our church in Albany. He loved tennis and actually tried to develop “felt” as a surface for tennis courts, very much like a grass surface. But as his condition worsened, he eventually had to retire from the company and his daily care fell to my mom’s province. That took a heavy toll on her and she retreated into her artwork which kept her sane. Eventually, thanks to the VA, my dad took on elder care and finally a spot in a VA hospital for his final days. At the end, I visited him, played my mandolin for him and told him I loved him. Tragically, I don’t remember him ever saying that he loved me.

My mom told me that I shouldn’t worry; his disease wasn’t genetic, but the effects of this disease remains in my psychological DNA. I learned during my teens to avoid conflict and to sublimate my anger and upsetting emotions. My father also thought that I was a homosexual and that misunderstanding led to a dramatic schism in our relationship. I’m sure my relationship and subsequent divorce from my wife suffered from my conflict avoidance. I never confronted Kim when she was doing something I considered misguided, and that led partly to our separation. I tried to support her outright, as an act of love and chose not to contest her decisions. That’s on me.

But, I have learned to tell my daughter Rosalie, son Jaimie, and even Kim, as well as those around me who really matter in my life that I love them. I am a better person for that and I cherish the times we spend together.

My father was a good man, served in WW II, raised three fine children, loved my mother, provided the means for her to explore her creative art, and supported my five years as an Arts-Engineer at Lehigh. I wish his later years were not as tough as they were and I regret our separation.

My father was a good man, served in WW II, raised three fine children, loved my mother, provided the means for her to explore her creative art, and supported my five years as an Arts-Engineer at Lehigh. I wish his later years were not as tough as they were and I regret our separation.